It seems that the popularity of deliberate practice in teacher development is only growing. I regularly hear school leaders debating how to best incorporate deliberate practice into small group professional development (PD) sessions, whole school PD, or as a part of instructional coaching.

In fact, some teacher educators have argued that instructional coaching is essentially a vehicle to deliver deliberate practice in a ‘wrapper’ of complementary elements. I’d say that this is a fairly bold claim, since whilst a number of instructional coaching approaches feature deliberate practice as a core mechanic (e.g. Bambrick-Santoyo, 2018), many do not (e.g. Allen et al., 2015).

All told, I get the feeling that it has become an unquestioned assumption that school and trust leaders should look to incorporate deliberate practice into their teacher development approaches wherever possible.

However.

As a teacher educator, I worry about the increasingly common use of the term in discussions in schools and teacher development organisations. There are a couple of issues I think are particularly worth examining in this three-part post:

Issue 1: Do we all mean the same thing when we’re talking about deliberate practice?

Issue 2: Is what’s happening in teacher development really ‘deliberate practice’ as defined by researchers?

Issue 3: Is deliberate practice relevant to the challenges of developing expertise in teachers?

In this post I’ll be considering the first question – what do we mean when we say ‘deliberate practice’ in the context of teacher development?

Know; Do; Perform

Teacher educators have historically grappled with a number of challenges when looking to develop the skills, knowledge and impact of teachers. One particular challenge, dubbed the ‘Knowing-Doing gap’, is summed up by Doug Lemov and colleagues in Practice Perfect:

“We would show one short video clip after another of superstar colleagues demonstrating a particular technique. We would analyse and discuss, and once our audience understood the technique in all of its nuance and variation, we went on to the next technique. Participants told us they had learned useful and valuable methods to apply. But then we noticed something alarming. If we surveyed the same participants three months later… they still knew what they wanted their classes to be like, but they were unable to reliably do what it took to get there. Just knowing what they should be doing was not enough to make them successful.”

Lemov, Woolway and Yezzi, 2012

Faced with this challenge, teacher educators explored what they might be able to learn from research about this problem, and as I’ve written about before, found the teacher development literature to be largely lacking in high-quality causal evidence.

So, the search expanded to the wider field of expertise development, where parallels emerged between teaching and other ‘performance professions’.

Performance professions are defined as those in which practitioners execute their roles live. Examples include professional athletes and musicians, therapists, surgeons and pilots. When undertaking their job or role, in performance professions practitioners are unable to press pause or to ‘rewind and have another go’.

Mistakes in these arenas are relatively high-stakes. Trial and error when doing such jobs can be costly, whether that means risking hard-won relationships with therapy clients, or even higher-stakes, as in the case of surgery.

Teaching, many have argued, is similar. During a lesson we cannot pause at a critical decision point and take a few hours to deliberate over what to do next; likewise, we cannot restart a lesson to try again.

The stakes may be less life-threatening than in a surgical theatre, but if we are unsuccessful in our educational efforts we cannot reclaim the lesson time spent – in order to reteach ideas that didn’t work the first time we need to encroach upon future (and finite) curriculum time.

Practise, deliberately

It turns out that researchers in the field of expertise development have thought about how we might develop expertise for these kinds of professions quite a lot.

In the 90s, Anders Ericsson argued that expertise is a product not of natural talent, or context, but of the amount of practice people do (popularised by the 10,000 hours principle in Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers). The argument is that, particularly for performance professions, judicious use of low-stakes practice serves a vital role in developing practitioners’ skills to maximise the chance that subsequent high-stakes (‘live’) work is as successful as possible (Ericsson et al., 1993).

NB: Here, low-stakes means that the consequences of making mistakes are minimal compared to when we go live – in surgery, mistakes in low-stakes practice won’t cause harm to patients; in a school context, pupil learning is not at risk if we make errors in the training room.

Ericsson termed the kind of practice most likely to drive improvements deliberate practice, and he argued it has a set of characteristics that distinguish it from other, less effective forms of practice.

More on this in the next post, but before we get to that there’s a more fundamental question to consider – do we agree on what we mean when we talk about deliberate practice?

Issue 1: Do we all mean the same thing when we’re talking about deliberate practice?

If you ask 30 educators how they would define deliberate practice, it turns out you get 30 slightly different interpretations – I can confirm this having run this experiment a number of times.

To illuminate this, we can compare a few definitions of deliberate practice from across the sector:

A) An instructional coaching definition

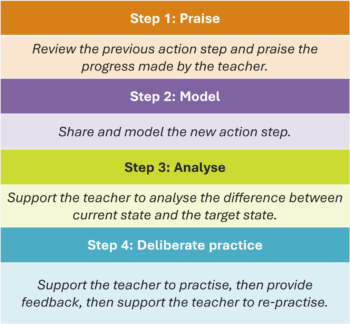

Let’s start with a simple instructional coaching model (I’ve borrowed this one from an Early Career Teacher programme):

It’s debatable how to interpret this, but Step 4 seems to imply that deliberate practice means: a practice opportunity, followed by feedback, and then further attempts at practice.

B) A definition from NPQ evidence summaries

What about the new and reformed NPQs (National Professional Qualifications) in the UK? The following is an excerpt from an NPQLTD (Leading Teacher Development) evidence summary, discussing deliberate practice:

“Modelling and then teachers rehearsing a teaching strategy, often referred to as deliberate practice, is one of the most effective ways to improve…”

NPQLTD evidence summary

This implies that deliberate practice means: first modelling a new approach, followed by a practice opportunity (here called rehearsal).

Note that modelling has been added in this definition; but, there’s no mention of deliberate practice including feedback in this version.

C) The artist formerly known as Twitter

The third, and perhaps simplest definition is one that many use – this is one I’ve picked from X that reflects the general sentiment:

“[Deliberate practice] is just practising without the kids there.”

This final definition is a common way that the term seems to be interpreted: that deliberate practice simply and solely refers to the act of low-stakes practice.

So, we have a range of more or less involved definitions of how deliberate practice is interpreted in teacher development – some involve the role of modelling, some feedback, and all seeming to include the idea of low-stakes practice.

Is this a problem? I think so, yes.

Getting on the same page

The importance of shared language in developing teaching practices is often emphasised by teacher educators – if I say ‘I’m trying to use worked examples and they’re not working for me’, and you say ‘oh, they work for me really well’, the quality of this professional conversation is going to be pretty dependent on us having the same understanding and definition of worked examples.

The same holds in in teacher development. When discussing deliberate practice, we risk talking at cross-purposes if we assume that everyone else has the same definition of the concept that we do.

Using the same term to refer to different approaches (the ‘jingle’ fallacy) is problematic as it reduces our ability to have accurate, professional conversations about teacher development work.

What can we do about this?

The solution? To me it’s simple – don’t say deliberate practice!

Instead, use clear, concrete terms to say what we actually mean when we’re talking about teacher development approaches:

- If you’re planning a PD session where teachers will practise, get feedback, and then re-practise… then just say that!

- Or, if you want to plan for the combination of first modelling a new approach, and then supporting teachers to practise it… then just say that instead.

- Or, if you’re using the term ‘deliberate practice’ to solely refer to the element of PD where teachers practise in a low-stakes way… why not just say ‘practice’ or ‘rehearsal’? It’s simpler, more concrete, and reduces the risk that people misinterpret what you’re doing.

Whilst this simple change aims to address the problem of shared language, there are further issues to be explored when it comes to practice-based approaches to teacher development.

In particular, it seems likely that many of the various ways that low-stakes practice is being implemented in professional development bear little resemblance to the original definition of the approach that comes from the literature. This is what I’ll be unpacking in my next post in this mini-series on deliberate practice.

What do you think?

How does this resonate with your experiences? Have I missed anything? There are plenty of nuances and details to dig into in future posts; let’s start a conversation and push this forwards! Find me here on X/Twitter, here on Threads, or leave a comment below.

References

- Allen JP, Hafen CA, Gregory AC, Mikami AY and Pianta R (2015) Enhancing Secondary School Instruction and Student Achievement: Replication and Extension of the My Teaching Partner-Secondary Intervention. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness 8(4): 475-489.

- Bambrick-Santoyo P (2018) Leverage Leadership 2.0: A Practical Guide to Building Exceptional Schools. NJ: Jossey-Bass.

- Ericsson KA, Krampe RT and Tesch-Römer C (1993) The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review 100(3): 363-406.

- Lemov D, Woolway E and Yezzi K (2012) Practice Perfect: 42 Rules for Getting Better at Getting Better. NJ: Jossey-Bass.

Credits

Thanks to Sarah Donarski (blog here) for pushing me to start this mini-series after a run-in at ResearchEd Warrington 2024!

Teaching can learn from other performance profession for sure BUT unlike sport, music, drama pros, teachers are always performing. The others perform occasionally and practise in the interim. As a profession we don’t seem to have decided what definitively works and therefore designing practice drills based on expert performers is more problematic. In addition, DP requires a coach to be present and this is simply not the case in teaching.

Skills may be seen on a continuum of open to closed skills. Whilst some skills in teaching are closed and can be practised in isolation, the majority are determined by the environment and are for me best practised live. Practising questioning without the children? No! The skills is in the response they give.

In a time poor profession I’m not convinced we have adequate time to practise in isolation beyond the tokenistic.

Even Ericsson doubted its use in education as he saw it as something that could only be used in domains where there were clearly defined experts and associated defined expertise

Great post

Chris

Thanks Chris, I appreciate it. And, have you been reading my notes…?? Lots of stuff here that I completely agree with and will be discussing on later in this series (in post 3 largely).

You once wrote on Twitter (a fair while back) about the ratio of practice time-performance time in teaching and it was something that kicked off a lot of this thinking for me, so thank you for that. I definitely worry about any overly confident direct comparisons between other performance professions and teaching – in terms of the opportunities we have to develop teachers, that is.

In terms of the relevance and utility of practice for developing expertise in teaching, I think we may have slightly different conclusions (which is great for healthy debate!). Whilst I definitely agree that a) we have a pretty different development landscape to most of the other professions that teaching gets compared to, and b) practice is far from a magic-bullet for PD, I’m not sure that low-stakes practice is necessarily worthless in teacher development. I actually think that it *can* help develop not only more routine aspects of teaching, but even more adaptive elements of practice. All of this is definitely heavily caveated by the time constraints you mention though, for sure. I’m going to write more about this (probably not in this series, but in a subsequent post) to try to explain my thinking in more detail, so will really value your thoughts and any challenges!