Teacher educators face a dilemma.

They know that the quality of teachers affects pupil achievement, and that professional development can improve both teaching and subsequent pupil learning (Chetty et al., 2014; Cordingley et al., 2015).

However, they also know that much historical professional development has failed to improve teaching (TNTP, 2015). This is combined with the universal barrier of a lack of time – particularly when working with in-service teachers.

As a result, teacher educators are often tasked with evaluating how best to use the (often, vanishingly small) time available for teacher development.

Grappling with the ‘how’ of teacher development

Consider two hypothetical school leaders:

Nathan is a secondary assistant principal for T&L, deliberating between two forms of teacher education to overhaul the PD offer at his school: ‘lesson study’ and ‘teacher learning communities’ (TLCs). From what he’s read, lesson study involves teachers collectively planning a lesson, which is then delivered, observed and discussed. And, in TLCs, teachers periodically collaborate to examine their current practices, learn new approaches, and plan for future change.

Khadija is the professional development lead for a trust of primary academies. She has decided to pursue ‘instructional coaching’ as the core of the trust’s development offer. She is deliberating between a number of potential coaching protocols: the ‘Six Steps for Effective Feedback’ model (Bambrick-Santoyo, 2018), the ‘Impact Cycle’ (Knight, 2017), or an adaptation of the model the trust has started to introduce for early career teachers.

Both want to make the most of limited development time by drawing on best practices from across the sector; however, this aim may be hindered by two assumptions.

The first is that we should focus on ‘forms’ of professional development, as in the case of our hypothetical assistant principal Nathan. Forms provide names or labels for approaches – such as lesson study, TLCs, or instructional coaching (Sims et al., 2021).

A focus on forms can be problematic because the same label can obscure important differences in practical approaches. For example, rehearsal (sometimes called deliberate practice) is an essential component of Bambrick-Santoyo’s ‘Six Steps for Effective Feedback’ instructional coaching model, yet it does not feature in Knight’s ‘Impact Cycle’ approach.

Teacher educators risk falling foul of an illusion of agreement, where we assume that our interpretation of an approach (in this example ‘instructional coaching’) is the same as everyone else’s.

A tempting solution to this is to argue that we should provide greater specificity by focusing on the details of the specific protocol or framework being implemented – as described in the case of our trust lead Khadija.

However, this second assumption leads to a focus on a range of surface-level characteristics. Whilst some of these may be integral to the development of teachers’ expertise, others may be ‘causally redundant’ (Sims & Fletcher-Wood, 2020), and fail to play a part in improving teaching.

Defining teacher development by its observable characteristics means we are unable to distinguish between irrelevant features and the ‘active ingredients’ that make it tick.

In both cases, by not being clear about what is going to cause teacher learning, we may be leaving it to chance.

Reframing teacher education in terms of ‘mechanisms’

Until recently, these two approaches – framing PD in terms of forms or observable characteristics – are largely all that have been available to teacher educators.

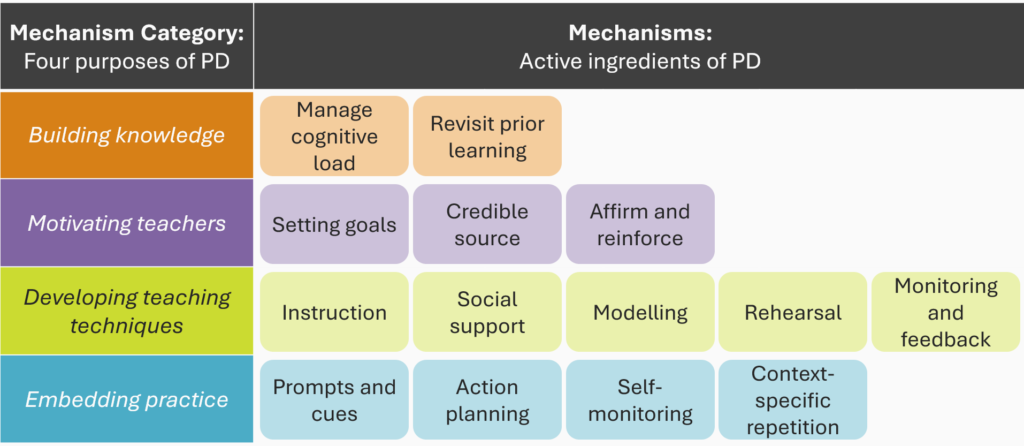

To address this limitation, a framework has been proposed by a joint group from UCL and Ambition Institute in the EEF Effective Professional Development guidance report (EEF, 2021).

This framework proposes that effective professional development rests upon a set of fundamental active ingredients, or ‘mechanisms’. There are 14 such mechanisms that the report argues play a causal role in professional development that improves pupil learning.

These are categorised into four underlying purposes that teacher development serves: Building knowledge, Motivating teachers, Developing teaching techniques, and Embedding practice.

The report concludes two key findings.

- Finding 1: The more mechanisms a PD approach draws on, the greater the subsequent impact on pupils.

- Finding 2: A PD approach that includes mechanisms that draw on all four purposes of PD may be more impactful than those which do not.

For teacher educators, the benefit of a mechanism-first approach is that, rather than having to look for the ‘next big thing’ to overhaul their PD programmes, they can instead evaluate the efficacy of existing practices.

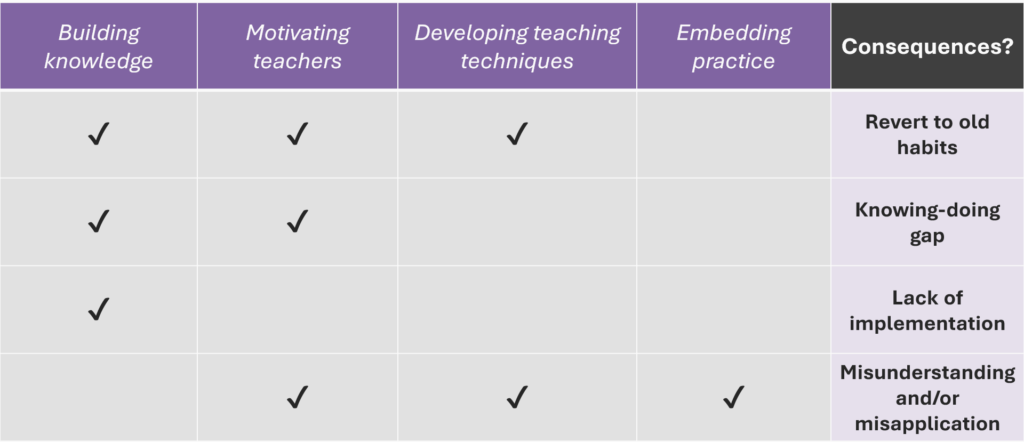

The report also offers an overview of the likely consequences of any given purpose of PD being missed out:

This aspect of the report is particularly useful to teacher educators. They might ask themselves, ‘Which of these consequences do I recognise in my setting?’, and ‘Which mechanism categories are currently unrepresented in our PD, and how might we integrate those into our current offer?’

Implications for teacher development

To put this into practice, Nathan might start by considering Finding 1, asking himself: Which mechanisms are present in my current PD offer?

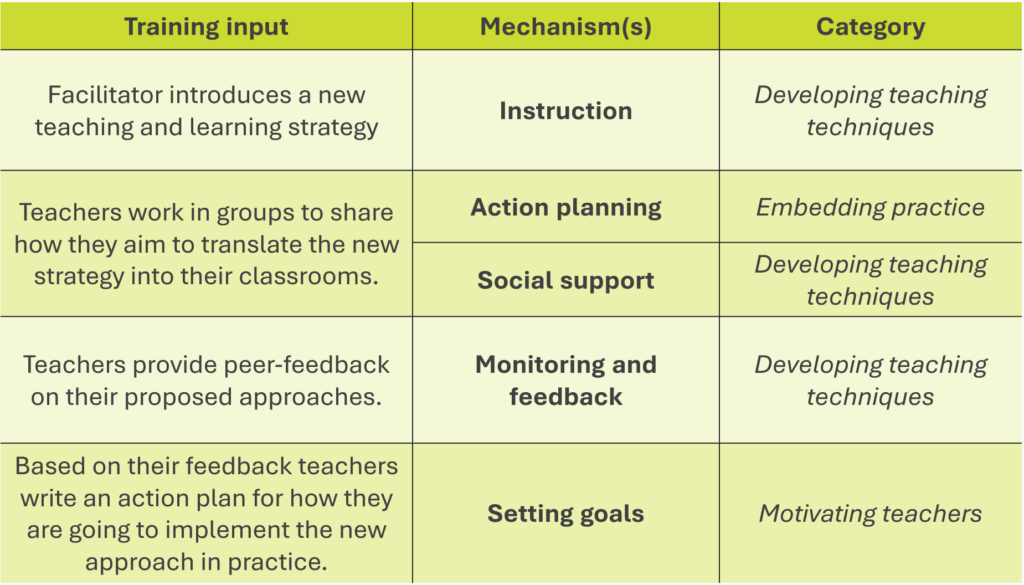

His current approach is as follows:

Sims et al. (2021) define lesson study as consisting of the Action planning, Social support and Monitoring and feedback mechanisms, with TLCs comprising Action planning, Social support and Setting goals. In light of this, Nathan realises that neither of these forms offer additional mechanisms to his current approach.

By considering the underlying mechanisms, rather than the forms, Nathan concludes that a move to either of these approaches may not actually alter the impact of his PD – beyond a superficial change in name.

Such a change may also contribute to initiative fatigue. Scrapping existing systems that staff have been asked to invest time and energy into may disillusion and demotivate teachers who fail to see the need to introduce ‘yet another shiny new thing’.

So, Nathan instead resolves to refine his existing approach by considering Finding 2, asking himself: Are there any mechanism groups that are currently unrepresented in my PD approach?

He notices that at present his PD fails to draw on any mechanisms from the ‘Building knowledge’ category (see Figure 3) – perhaps this is the reason his current approach is not yielding the desired success.

From learning walks, he recognises the consequence warned of in the EEF’s guidance report: that failing to include mechanisms from the ‘Building knowledge’ category can lead to misapplication of new approaches (see Figure 2). Previously he has tried to address this issue through increased monitoring and accountability; a mechanism-driven approach suggests that this might be better addressed by an iteration to the school’s PD structure.

Nathan decides to incorporate the Revisit prior learning mechanism from the ‘Building knowledge’ category. To do this, he plans to start each session by asking teachers to retrieve and revisit the underlying purpose of the strategy covered in the previous session.

Supporting staff to understand the role new strategies play in supporting learning in their classrooms should help them to increasingly make judicious choices about when to use new teaching approaches, and how, and for what purpose (Kennedy, 2016).

A more nuanced and evidence-informed approach to teacher development

Considering the design and delivery of teacher development through the lens of the EEF’s mechanisms can allow us to reconsider existing approaches to professional development by considering what’s causing the impact, or lack thereof, that we see amongst our staff and students, without necessarily requiring a drastic overhaul of our current practices.

However, I do worry that the findings from the guidance report may be challenging to translate into practice in some cases, potentially limiting its utility to teacher educators and school leaders. I’ll be examining this problem in my next post, which I’d love to hear your thoughts on.

What do you think?

How does this resonate with your experiences? Have I missed anything? There are plenty of nuances and details to dig into in future posts; let’s start a conversation and push this forwards! Find me here on Twitter or leave a comment below.

References

- Bambrick-Santoyo, P. (2018) Leverage Leadership 2.0: A Practical Guide to Building Exceptional Schools. NJ: Jossey-Bass.

- Chetty, R., Friedman, J. N., & Rockoff, J. E. (2014) ‘Measuring the impacts of teachers I: Evaluating bias in teacher value-added estimates’, American Economic Review, 104(9), pp. 2593-2632.

- Cordingley, P., Higgins, S., Greany, T., Buckler, N., Coles-Jordan, D., Crisp, B., Saunders, L., & Coe, R. (2015) Developing great teaching: Lessons from the international reviews into effective professional development. London: Teacher Development Trust.

- EEF (2021) Effective Professional Development: Guidance Report. London: Education Endowment Foundation. Available from: https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/education-evidence/guidance-reports/effective-professional-development

- Kennedy, M. (2016) ‘Parsing the Practice of Teaching’, Journal of Teacher Education, 67(1), pp. 6-17.

- Knight, J. (2017) The Impact Cycle: What Instructional Coaches Should Do to Foster Powerful Improvements in Teaching. CA: Corwin.

- Sims, S. & Fletcher-Wood, H. (2020) ‘Identifying the characteristics of effective teacher professional development: a critical review’, School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 32(1), pp. 47-63.

- Sims, S., Fletcher-Wood, H., O’Mara-Eves, A., Cottingham, S., Stansfield, C., Van Herwegen, J. & Anders, J. (2021) What are the Characteristics of Teacher Professional Development that Increase Pupil Achievement? A systematic review and meta-analysis. London: Education Endowment Foundation. Available from: https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/education-evidence/evidence-reviews/teacherprofessional-development-characteristics

- TNTP (2015) The mirage: Confronting the hard truth about our quest for teacher development. Washington, DC: The New Teacher Project.

Credits

Thanks to Steve Farndon for helping to develop, challenge and refine my thinking on these ideas, in addition to the wonderful Cohort 5 of Ambition Institute’s Teacher Education Fellows.